There is one certainty we all share: every life ends. Along the way, most of us will also experience the death of someone we love.

Despite this shared reality, death is one of the hardest things to talk about. It’s unfamiliar, emotionally charged, and impossible to fully understand in advance. No one comes back to explain what it was like. When death moves from something abstract to something personal, it can feel overwhelming—emotionally, physically, and spiritually.

That’s why listening to people who work closely with death can be so grounding. Their experience helps replace fear with understanding, and confusion with compassion. Learning about death before we are forced to confront it can help us grieve more gently and approach our own mortality with less anxiety.

In conversations with hospice and palliative care physicians, nurses, and social workers, I was comforted, challenged, and surprised. Many of the most common fears about death are rooted in misunderstanding.

Dying Is Usually a Process, Not a Moment

Movies often portray death as quiet and instantaneous. In reality, dying from natural causes is typically gradual. Bodies change over time—breathing shifts, responsiveness fades, appetite disappears—and eventually, the person slips away.

These changes can be unsettling for families who don’t know what to expect. In hospice settings, one of the most common sources of distress is the fear that something is “going wrong,” when in fact what’s happening is normal.

For example, people nearing death often stop wanting food or water. This is not starvation—it’s the body shutting down. Trying to force eating or drinking can actually cause discomfort and emotional strain during a time that calls for gentleness.

Similarly, medications like morphine are often misunderstood. They do not cause death; they relieve pain and ease breathing when someone is already dying. The goal is comfort, not acceleration.

Regret Often Comes From Avoidance, Not Mistakes

Many families carry regret—not because they did the “wrong” thing medically, but because fear made it hard to be present.

Loved ones may shut down conversations about dying because they don’t want it to be true. But for the person who is dying, being able to talk openly—to be seen, heard, and held—can matter deeply.

At the same time, there is no single “right” way to show up. Not every relationship is close or healed, and no one is obligated to perform a version of closeness that isn’t authentic. Grief is personal. Presence looks different for everyone.

There Is No One Right Way to Die

Some people want quiet. Others want music, conversation, laughter, or even celebration. Comfort isn’t a mood—it’s personal. Assumptions about what a dying person “should” want often miss what actually brings them peace.

Preferences around death vary just as much as preferences around life. Some people value longevity at all costs. Others value comfort and quality over time. Neither is wrong.

What matters is that people are given the chance to reflect, communicate, and be honored in their choices.

Planning Matters More Than We Think

Many people say they want to die at home, yet a significant number of deaths happen in intensive care settings after aggressive treatments that don’t align with the person’s values.

Talking about death early—long before a crisis—makes it more likely that wishes will be respected. Advance care planning isn’t just paperwork. It’s identifying trusted people, having honest conversations, and revisiting them over time.

Planning doesn’t mean controlling death. It means reducing unnecessary suffering and confusion for everyone involved.

Hospice Is About Living Well Until the End

Hospice and palliative care are often misunderstood. They are not about giving up. They are about comfort, dignity, and support.

Palliative care can be provided at any stage of serious illness. Hospice care is for those nearing the end of life—but people can live in hospice care for months, sometimes longer, while experiencing improved comfort and emotional well-being.

Reducing pain and distress often allows people to conserve energy for connection, reflection, and meaning.

We Cannot Control Death—and That’s OK

Modern medicine is powerful, but it cannot eliminate death. When we believe it should, we often meet loss with anger, shock, or shame.

Those who experience the least distress at the end of life are often not the ones who controlled every detail—but those who lived fully, were witnessed, and felt seen.

At the same time, it’s okay not to be ready. It’s okay to love life until the very end. Death can be both heartbreaking and meaningful. It can be peaceful and painful. It can be sad and still right.

Holding space for all of that—without forcing a single narrative—is part of what makes us human.

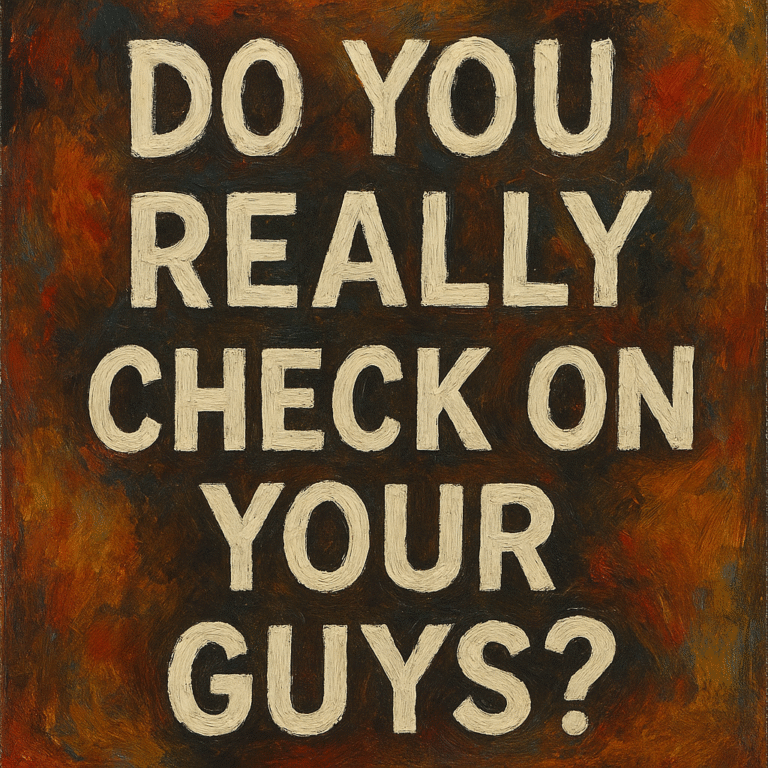

I am going to be starting a Social Club series called Knight Club, a non judgemental space where you can come hangout, listen to music, have some snacks and drinks with me and fellow brothers alike who hunger for space and peace.